If you took a close look at your own DNA, what might you find?

For 2025 Mark Foundation Emerging Leader Award winner Ansuman Satpathy, MD, PhD, the answer turned out to be a groundbreaking discovery.

In a recent PNAS paper, Satpathy and his collaborators challenged a central tenet of genetics: that synonymous DNA mutations, which alter the genetic sequence but don’t change the resulting proteins, are functionally insignificant or “silent.” Satpathy’s paper showed that under the right conditions, this isn’t true — and the proof was in his own blood.

A Discovery Hidden in Plain Sight

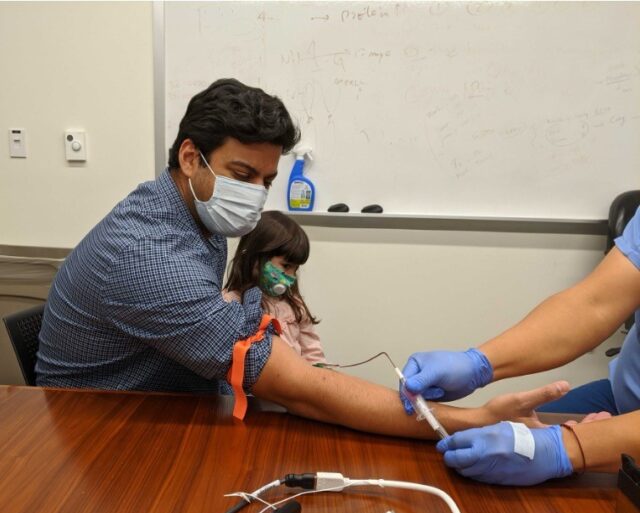

The discovery began with an ongoing study designed to answer a fundamental question in immunology: how do our immune systems change over time? Satpathy, a physician-scientist and associate professor at Stanford University, and his collaborator and former postdoctoral fellow Caleb Lareau, PhD, now an assistant professor at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, are tracking immune cell clones over a period of several years in a group of healthy volunteers, including themselves, by using tiny, naturally occurring variations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) as cellular barcodes. The long-term goal, Dr. Satpathy explains, is to understand basic processes like hematopoietic turnover and how clones change over time with infections or vaccination.

But an unexpected finding came sooner than the team expected when Lareau noticed a highly unusual variant in a data set and realized that it came from Satpathy’s sample.

“Caleb messaged me at 11 p.m. on a Monday night and said he’d found something that could be big, and it was in my DNA,” Satpathy recalls.

The variant, a synonymous mutation in a gene called MT-CO1 which is essential for energy production, was present in nearly half of Satpathy’s immune cells — but was distributed unevenly across cell types. This was strange. If the variant was truly silent, why would it show up at different rates in specific types of immune cells?

A ‘Wobble’ in the Cellular Engine

Using single-cell multi-omic technologies to create high-resolution molecular profiles, the team found a striking pattern. The mutation was mostly depleted in one specific population: CD8+ effector memory T cells, a type of immune cell essential for fighting infections and cancer. These cells appeared to be actively purging themselves of the mutation.

The reason came down to a concept that Satpathy and Lareau both remembered from introductory biology courses — “wobble.” Mitochondria have a limited set of tools for translating genes into proteins. The silent mutation forced a specific mitochondrial tRNA to use an inefficient “wobble” base pairing — a pairing between two nucleotides that does not follow Watson-Crick-Franklin base pair rules — to read the genetic code. For most cells, this minor inefficiency is irrelevant. But as Satpathy and Lareau discovered, for CD8+ T cells, which have immense metabolic and energy demands, it is a critical flaw. The wobble pairing causes mitochondrial ribosomes to stall, impairing the cells’ ability to generate energy and putting them at a severe competitive disadvantage.

“We found that what’s ‘good enough’ for most cells to function is typically not good enough for a subset of T cells,” says Lareau. “This mutation may be totally fine in the skin or in the liver, but in a T cell, it turns out to lead to negative feedback.”

The Power of ‘N of 1’

Satpathy argues that the findings prove the value of an approach he has long championed: the deep analysis of a single individual, or an “N of 1” study. Rather than relying on massive datasets to find statistical trends, Satpathy says that the latest high-resolution technology and methods make it possible to uncover deep mechanistic insights from a small, well-characterized sample.

This approach challenges the conventional wisdom that large sample sizes are always required for meaningful discovery, a hurdle Satpathy has encountered before. One of his earlier papers — which changed the field’s understanding of T-cell responses to PD-1 blockade therapies in cancer patients — received initial pushback because it was based on samples from just 11 patients. However, those findings revealed a fundamental insight into how immunotherapy works that has since been confirmed in thousands of patients.

“I always had the view that if you go deep enough on the individual, you’ll find really novel biology,” Satpathy says. “That’s truly what motivates me and my lab.”

Driving Scientific Inquiry with Foundational Support

The idea that deep, mechanistic studies—even in a single person—can reveal universal biological truths is the philosophical thread connecting this discovery to the research supported by Satpathy’s Emerging Leader Award (ELA).

The ELA grant funds Satpathy’s work developing a novel approach to engineering “synthetic” T cell states with enhanced anti-tumor activity. While immunotherapy has revolutionized cancer treatment in recent decades, its effectiveness is often limited when T cells become dysfunctional or “exhausted.” Satpathy aims to build on his earlier work on synthetic transcription factors to create new T cell states that are superior cancer fighters. Additionally, his team plans to develop a comprehensive atlas of these synthetic T cell states and use machine learning tools to refine their engineering approach, creating valuable new resources for the field.

Ultimately, Satpathy says that both the ELA project and mtDNA study share the same goal: “Going from a patient to a broader genetic insight and then bringing that insight back to the patient again in a new treatment.”

This work is a testament to what can happen when researchers have the flexibility to pursue unexpected scientific paths. Foundational support like that provided by the Emerging Leader Award gives scientists the freedom to explore where the data leads. For Satpathy, that freedom is everything.

“The reason that we’re scientists,” he says, “is that we’re driven to explore questions that no one else has been able to figure out, even at the most basic level. Following those ideas is what leads to the excitement of discovery.”